On platforms

Dr.Thomas Morgan Evans

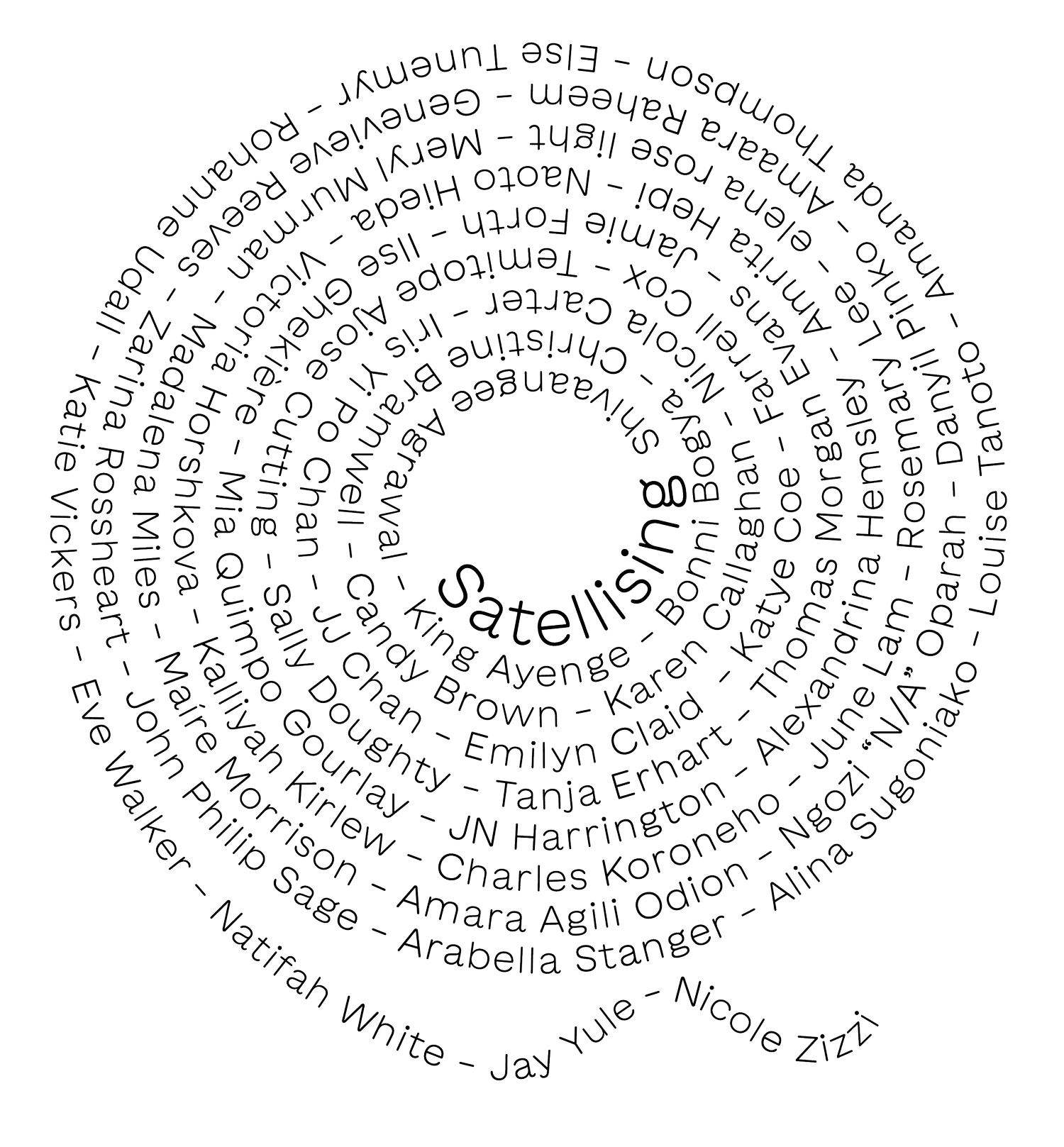

Image: Genevieve Reeves. Satelliser in performance at Baltic CCA. Coworkers: Bonni Bogya, Ngozi “N/A” Oparah, Emilyn Claid.

I am watching a child, of around five years of age, as he watches the dancers that make up J N Harrington’s Satelliser: a dance for the gallery, at the Baltic Contemporary Arts Centre. Leaving his parents, who had been crouched by his side, he crosses the invisible threshold that separates the spaces of spectatorship and performance. He runs into the space he had viewed, he runs between the dancers he had been watching: up and down, in a straight line between his parents and the dancers and back again. There is no music to accompany the dance but he makes rhythmic expressive exclamations. This provides a soundtrack which the dancers reciprocate through the yoga-like movements they make. The dancers are able to adjust the phrase they are performing so that it replies to the sound. Noticing this, the child then begins to make movements with his arms that mimic the gestures of the dancers. No longer running in straight lines, he begins to move into rather than through the space in the gallery, which he now holds confidently, following the movements of the dancers. The dancers respond, the short routine has built-in flexibility that allows them to step towards the child by directing their pivoting and stepping movement in his direction. It is clear he is in the centre of a web of meaning.

There is a moment of tension, amongst audience members at least, when it feels being viewed might become too much for the little boy. We had become enraptured in what another writer present has said was the ‘the best moment of audience interaction I think I’ve ever seen’.¹ This pressure is soothed by the dancers, they soften their bodies, fall back slightly on their heels, make more space for the boy. The dance continues, the conversation goes on as he continues to dance.

His mother and father are crying and smiling as they watch, this seemed like a special occasion for them. When their son has had enough, and enters the more intimate body-space between his parents who have been awaiting his return, his mother uses sign language with him as she speaks and the little child turns back around to the performers to say thank you. Only at that point, when these two other languages were encountered, did I wonder if the child had a learning difference. Whether this was the case or not, what we had seen was a lucid and articulate coming into concert.

Image: Gillie Kleiman. Satelliser in performance at Baltic CCA. Coworker: J N Harrington

Satelliser: a dance for the gallery is a work commissioned for touring in 2019 as part of the CONTINUOUS Network, a collaboration between Siobhan Davies Dance, the Baltic Contemporary Arts Centre, and a network of other regional galleries around the UK. The series aims to give visitors to these galleries an experience of experimental independent dance; it also provides an opportunity for the increasingly many choreographers whose work bridges art and dance.

Satelliser is comprised of a succession of phrases performed in a unison throughout gallery hours by a rotation of 10 or 11 female and non-binary dancers whose ages range from 22 to 70 years old. These phrases are mobile; the dancers play with their orientations (a phrase of Harrington’s that I think has abounding resonance) so that performers can engage with gallery visitors, approach them, or move in relation to each other.

Crucially the work is literally also one long sustained conversation, the dancers talk, and this talking provokes the ‘relational experiences’ which are held between the group and the audience. The topics discussed during my visit included the forms of exploitation different co-workers had faced in their careers, and what the meaning of ‘discipline’ was. This is in addition to those exchanges, like that described above, which are harder to name or describe.

The title of the work, Satelliser, refers to a rarely used French transitive verb which means to ‘put into orbit’. The association meant here is not of ostracisation but, instead, of a body in mobile relation to a system of connected bodies that is in some way propelled or motivated. Satelliser describes very well the example above where the child might be said to have entered the work’s ‘orbit’. Satelliser’s planetary poetics also suggests something of its make-up: its extensity, its encounter of ages, backgrounds and positionalities; the ‘play with orientation’ it allows. Relatedly, the term also describes the work of Satelliser as the dancers themselves enter into unison at the start of the day, tire, come off their staggered shifts, and then re-enter. Lastly, and most obviously, when the dancers talk their speech goes out into orbit and, through the open invitation that the dance makes to its audience, with smiles and open gestures, we are brought in, either as listeners or as respondents.

One way Satelliser might be viewed therefore, is as an investigation into what it is to speak and be heard publicly. In thinking about the work in this way it is inevitable that another term -- ‘platform’-- is summoned up and I think it might be productive to think about the work in relation to this term.

What, then, are the connotations of the idea of a platform as we encounter this term today? We hear of those who ‘use their platform’ to speak on subjects that concern them. These people have a platform by dint of their positions of power or influence, but the metaphorics of the term implies that what is said from their platform is in some way at a remove; typically they are speaking on behalf of someone else, or a group, or a cause. Increasingly what these positions of power amount to or are synonymous with is another kind of platform, the social networking service. Again, with this use of the term, we encounter metaphors of elevation and a certain kind of distance: the social media network is a platform on top of which discourse happens, for example. Yet despite this being how we are encouraged to think about platforms, in both instances we are confronted with mystifications. We know, for example, that when Ben Affleck uses his ‘platform’ to ‘solve’ the crisis in the DRC, Affleck had hired the services of the strategic consultancy firm williamsworks to find a suitable cause to take up. What I want to suggest, therefore, about the relationship between the power-body that ‘platforms’ public speech and the speech itself is that they are integral to one another, not separate or distinct; in both cases fluency and affluence are connected.

The costumes that the dancers wear in Satelliser echo some of this contemporary backdrop. They speak of the single-identity and homogeneity of the contemporary platform; its ability to objectify and spectacularise. The dancers’ loose neon tabards invoke both the steward and the gilet-jaune, connoting the performers’ role in ‘directing’ the flow of bodies and speech in public and, also, representing a coherent public themselves. Yet though the costumes might frame the work within a contemporary context that is all about platforms, the dance subverts its neoliberal logics.

One important feature of the blahblahblah-o-sphere of platforms is that speech is slick, crafted, curated; even when it stutters it does so expressively, articulately. Platformed speech is never mute. All speech tends towards the contradictory status of a personal public announcement. At the same time, the platform caters to specific forms of attention, that is both diminished (i.e. increasingly short) and invisible. To make your attention visible you have a binary choice: thumb up or thumb down.

By contrast I was struck by the differing kinds of attention the audience gave Satelliser. One couple I spoke to were convinced that the work had been scripted and marvelled at how the dance was choreographed to match what was being said. One could drift between different kinds of attention, perhaps making eye contact with a particular dancer at one moment, then watching the dance at another, then tuning in to the conversation at another. One thing that was extraordinary was how visible these different degrees and kinds of attention were to others. This is because the dancers reflected them. There were moments in which it was clear everyone had suddenly begun listening intently.

Image: Genevieve Reeves. Satelliser in performance at Baltic CCA. Coworkers: Shivaangee Agrawal, Karen Callaghan & Emilyn Claid.

Image: Genevieve Reeves. Satelliser in performance at Baltic CCA. Coworker: J N Harrington

The way in which Satelliser seems to be able to accommodate forms of engagement that are not proscribed, and forms of speech that are not fluent or slick, I would suggest presents a departure from the spheres of platformed speech we encounter elsewhere. Essentially, I want to suggest, this is a form of platforming where meaning can be made from positions of disorientation, and speech can be constructed and co-constructed through multiple forms of utterance and multiple forms of reception.

In this vein, Harrington’s work develops the anti-fluency of dance artist Yvonne Rainer’s pioneering work of the 60s, with its commitment to a disrupted as well as disruptive dance language. A member of the Judson Dance Theatre, Rainer used the everyday body and the everyday action, or task, to deconstruct boundaries between object and subject, art and life. Today, this informs the ‘constructed situations’ of what is now a canon of contemporary, gallery-based practices wherein performers engage with audience members in ways that reflect forms of social interaction outside the gallery.

Rainer’s expanded vocabulary emerged through a refusal of slickness, something that continued as she began to make films. These, equally, worked against easy listening and speaking, and commercialised modes of reception. Yet if Satelliser, likewise, refuses forms of (af)fluency, it acknowledges that the easy listening and easy speaking which Rainer’s work stood against is not ‘easy’ for everyone. In Harrington’s work we see an attempt to develop a new type of platform where neurotypical fluency and an easy ability to do, speak or attend is not necessarily a given.

Compared to Rainer’s work, Satelliser’s choreography might be described as benign because of this, it works hard to ensure that its proscribed engagements with the audience are not felt as confrontations. Unlike other recent experience-based work, Satelliser manages to disarm, but not deny, the forms of participatory self-consciousness involved in this kind of interactive work. One form of this self-consciousness occurs as you connect with a dancer, perhaps through eye contact or conversation, who, a second ago, you had been watching as if on stage; another occurs when you now realise you are now part of the spectacle as you make that connection and participate. In Satelliser both moments can be noticed, the shifts of power that are held within them can be reflected on, and they can be both surmounted or reverted on without judgement. It is not a stretch to say that experiencing crossing these boundaries, entering in and out of these frameworks, can be felt as a healing experience.

My contention with all of this is not to fit a reading of Satelliser to the admittedly magical experience I describe at the beginning. Instead, I want to suggest that this example demonstrates an incidence of confluence between the work’s deconstruction of normative forms of address and one particular child’s difference. Then, the work was able to hold non-normative forms of communication within and despite the gallery framework in which relations between viewer and viewed, subject and object, are normally very proscribed. It is this capacity that I want to suggest is key to the politics of this work. We all might relate to it, attend to it, or communicate through it, atypically. This does not mean we all engage the same way, quite the opposite, but unlike more normative platforms, Satelliser allows a coming-into-communicating through its whole, mobile system that allows for greater diversity. Such a description aligns to Erin Manning’s discussion of ‘creating the conditions for neurodiversity’ whereby the political stake is ‘not about creating a space for difference, a space where difference sequesters itself. It is about attuning to the… currents of creative dissonance and asymmetrical experience always already at work in, across, and beyond the institution.’² If the platform Satelliser creates can also be said to be an institution (and it is certainly given a platform by the institution of the gallery), then it is precisely the possibility of this attuning that Satelliser opens up.

Though we should avoid associating neurodiversity with concepts of disorder and pathology, we might consider the contemporary neoliberal platform as a form of social sickness; its symptoms expressed in the unanswerable statements of individuals who present themselves in singularity and autonomy. In this sense Harrington’s counter-platform investigates the therapeutic potential for connection whereby connection is not prefigured and given but in a state of embodied coming in to being. I want to end with a quote, again from Erin Manning, whose description of dance is used by Esté Klar in her discussion of facilitating her autistic son’s writing on a keyboard:

I respond not to your touch as such but to the potentiality your movement incites within my body. I respond to our reciprocal reaching-toward. If this touch is indeed approached relationally, chances are the couple will dance beautifully together. Body to body they will space time and time space. If not, it is likely that they will have difficulty locating one another.³

¹Kate Liston, ‘Janine Harrington: Satelliser -- a dance for the gallery’, Corridor8, 08/11/2021, https://corridor8.co.uk/article/janine-harrington-satelliser-a-dance-for-the-gallery/ (accessed 01/12/2021)

²Erin Manning, ‘Me Lo Dijo un Pajarito: Neurodiversity, Black Life, and the University as We Know It’, Social Text 136, vol. 36, no. 3, 2018, pp. 1-24, p. 2.

³ Erin Manning, Politics of Touch: Sense, Movement, Sovereignty, University of Minnesota Press, London, 2007, p. 88; quoted in Esté Klar-Wolfond Neurodiversity in Relation: An Artistic Intraethnography, diss., York University, Toronto, 2020.

Dr. Thomas Morgan Evans (he/him)

Thomas Morgan Evans teaches art history and theory at the Art Academy London and the Slade School of Fine Art at UCL. His research centres on contemporary art and public space in a global context, with a particular focus on questions of home and homelessness. He is the author of the book 3D Warhol: Andy Warhol and Sculpture, and is currently at work on new projects about contemporary art in Puerto Rico.