The right amount of distance

elena rose light

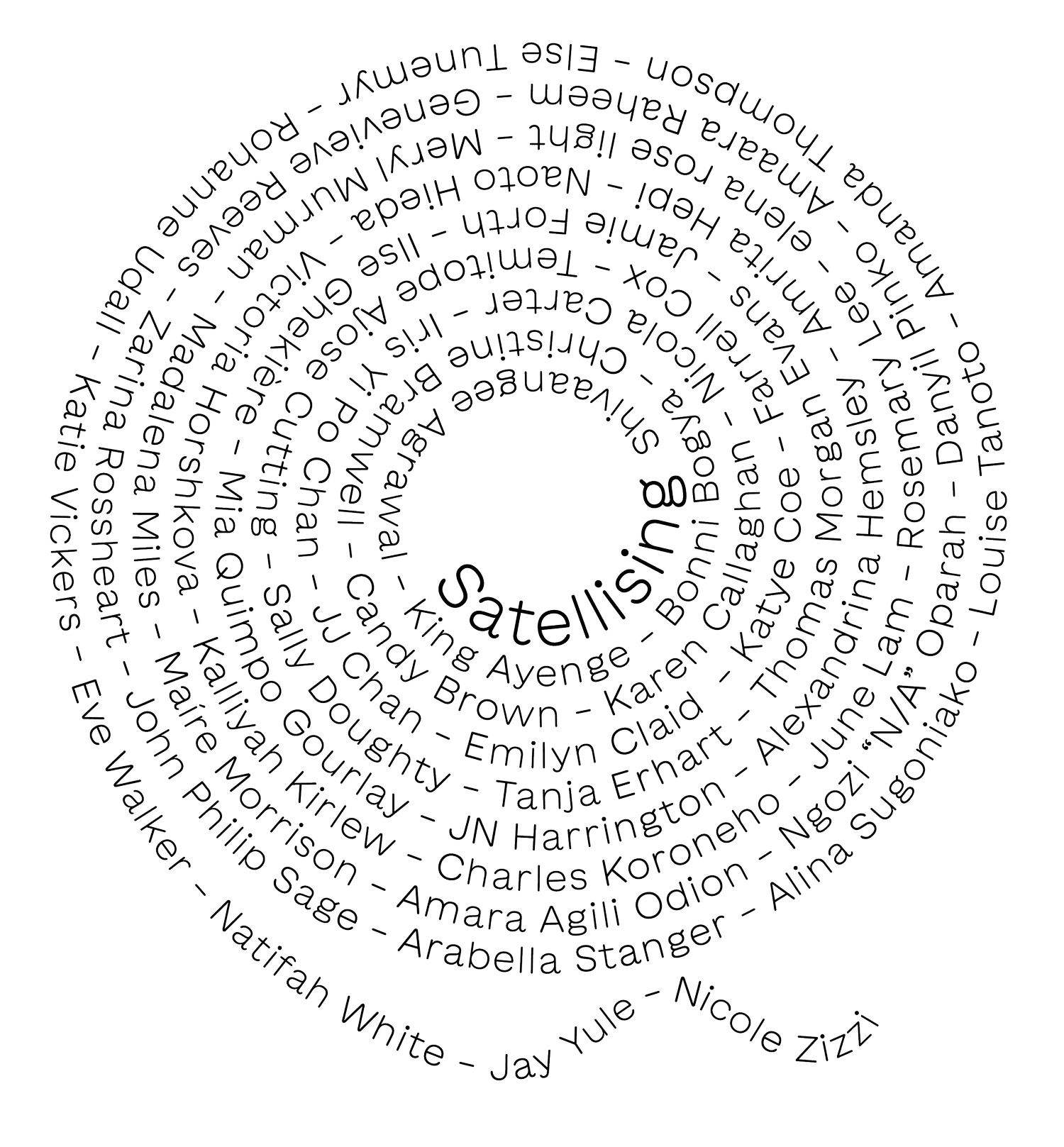

Image: Genevieve Reeves. Coworker elena rose light in performance at BALTIC CCA.

Their voices sound far away, as if echoing from the other side of a mountain, or from another mountain altogether, far off from the one I’m perched on. We’re miles apart and yet still able to hear one another.

In reality, I’m lying on the ground of my fourth-floor living room in mountainless Giessen, Germany, eyes closed, ears open, a mug of lemon-ginger tea balanced precariously on the rug next to me. It’s November 2020, and I’m logged into a virtual Satelliser: a dance for the gallery rehearsal with five of my co-workers and I gathered across different continents, finding synchronicity despite our divergent timezones and computer-room setups. I feel oddly close to them despite the literal gulfs between us.

Recently, I’ve been obsessed with the choreography of proximity. Human interaction is premised on this spatial dance, whether we’re negotiating the distance between seats in a theater or craving skin-to-skin contact from our caregivers as infants. In these past two years of COVID-19, we spend nearly every waking moment considering how close or far we are to other people. Six feet between each other. Oh wait, two meters. Is that right? Will that keep us safe?

In my personal relationships, I negotiate this balance. Some days, I feel too far from my identical twin sister in Lebanon; other days, too close to my co-habitating partner in Germany. Always, I aim to land on the amount of space that allows for care AND independence, understanding AND difference. It’s something my favorite Belgian psychotherapist Esther Perel talks about in the context of sexual and romantic relationships: Love likes to shrink the distance that exists between me and you, while desire is energized by it.

Perel’s erotics of distance is certainly at play in Satelliser. I can feel it in the visitors’ stares back at me, the way the boldness of my gaze is easily rendered seductive. I sense it in conversation with my co-workers, our flirty dynamic enabling us to flow through topics as we probe them for bits of interest. Perhaps this is why our rehearsals and performances sometimes feel like the best kind of first date, full of meandering conversation that dips into personal experience without yet creating deep emotional stakes.

This isn’t to say I don’t care about my co-workers. I may not know them that well as individuals—having only come to their acquaintance via this project—but, in fact, it’s exactly the airy space between us that allows me to empathize more generously. I have no agenda for our relationship, no expectations for their presence in relation to mine. Whereas if my twin shares something about her experience of the world, I might immediately consider how that affects our relationship. If my romantic partner shares something unique to their life, I might (in my worst moments) become insecure that I don’t understand, fearing that this profound difference in our subjectivities represents an insurmountable challenge to my desired intimacy with them.

In Satelliser, no such challenge arises, as intimacy is merely a byproduct of our goal to ongoingly converse. The orbiting choreography moves us into diverse proximities, freeing us from the imperative of perfect unison or understanding. Out of this distance, play emerges. For me, this manifests as an ease in discussing controversial topics with a diverse group of people—something I rarely find in other contexts. Somehow, this ease doesn’t minimize the depth we reach; our discussions deal with power and emotions and the intersections therein. Shit gets personal.

At Margate’s Turner Contemporary gallery, I mention that I’ve been tossing around the idea of using my childhood nickname “Len” more, as it holds my genderqueerness more visibly than “Elena” does. As soon as the words leave my mouth, I feel exposed for having opened up such an intensely personal choice to a public audience. Yet, just as soon as fear takes hold, the conversation spirals away onto some other topic, and I am flooded with relief. That’s the power of Satelliser: it lets you go there, while knowing that other people will join you there, and that just as soon you’ll move away from there and onto something else over here.

Choreographically, we move between here and there, near and far. Too close, and I almost run into Ngozi during a pirouette in the movement phrase. Near-collisions like this are full of drama and camaraderie, as though the parties involved are temporarily engaged in a danced inside joke. Another time, I stay too close to Bonni for too long, and our unison becomes too perfect. It reminds me of how I felt dancing in the corps de ballet as a child, my body and mind becoming swallowed into an indistinguishable mass of dancers. This homogeneity flattened the nuances of our individual forms. I take a step away from Bonni to find some breathing room; this way, we can connect as individuals—and still land that turn together.

Image: Kat Bridge. Coworker elena rose light & Ngozi Oparah in performance at Turner Contemporary.

If I situate myself too far from my co-workers, though, I get lost. I become unable to get a read of the room and maintain unison. This happens too when I accidentally tune out of the conversation, caught up in my own thought spiral or internal monologue. The experience reminds me of what we say when people die: They’ve left this plane of existence. They’re not here anymore. They’re gone. No wonder when I feel spatially distant my sense of embodied presence fades: I’m absent from the visceral vitality of human connection.

I notice a different kind of distance when a co-worker exits my purview. In Margate, I realize that Else is missing, gone off shift to take a break. I feel a momentary loss. Then, a sense of responsibility rises up inside me, wanting to fight against the “out of sight, out of mind” paradigm that disappears certain perspectives from political consciousness. What would Else have to say? I can’t know, but I silently commit to keep asking the question.

Nearness brings its own questions. When Shivaangee and Amanda re-enter the choreography at the beginning of their gallery shift, they begin dancing in close proximity to other coworkers, snuggling up in order to get acquainted with the topic of conversation. They’re like newborns, asking: what’s going on? Can someone clue me in to what we’re talking about? Their need for closeness brings us all into the intimate act of care. As someone who has been in the room for an hour, I try to orient them to the discussion so they feel invited to join in our communal labor. I trust they’ll do the same for me later in the day.

Over time, our collective weaves in and out of millions of proximities. During my break, I leave the Baltic gallery in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, walk across the Gateshead Millennium Bridge, try to feel as far away as I can from my co-workers for an hour. Back on shift, I do a face-to-face duet with Emilyn for a few seconds and feel my cheeks start to flush with the intensity of physical closeness. At every turn, I’m asking: how much space do I need or want? What are my coworkers signalling of their needs? The answers change, according to who I am, with whom, in what gallery, on what second, of what day.

There is one constant, though, both in the gallery and beyond: as long as we're questioning how near or far to be from one another, then we’re in an act of care. We will never know the right amount of distance to keep us safe, help us thrive, let us access that perfect blend of intimacy and individuation—because our needs are in constant flux. Rather than try to create a rule for this, Janine offers us a dance. It’s not perfect: our connections dissolve; the conversation becomes awkward; the visitors don’t know where to stand in relation to us. Still, we keep going, since we’ve committed to this spatial exercise in emergent strategy. We stay attentive to the space between us, in our dance and in our lives.

Image: Kat Bridge. Coworker elena rose light in performance at Turner Contemporary

elena rose light (they/them)

elena rose light is a choreographer and performer originally from Southern California (Micqanaqa’n). Their work is rooted in the potential for somatic empathy to reorganize systems of thought and governance, and has been presented by Abrons Arts Center, Gibney, Center for Performance Research, Brooklyn Arts Exchange, The Current Sessions, and Movement Research at Judson Church, among other venues. Elena has also performed in the work of Ursula Eagly, Bouchra Ouizguen, Tino Sehgal, Asad Raza, and others. They studied art history and French literature at Yale University, where they first became enamoured with experimental performance.